Ancient Egypt and the Nile River: The Lifeline of a Civilization

The Nile River transformed a desert into humanity’s greatest early civilization.

Ancient Egypt’s entire existence revolved around this magnificent waterway that flows northward through the heart of Africa. For over 3,000 years, Egyptian pharaohs, priests, farmers, and artisans built their lives around the Nile River’s predictable flooding cycles. The annual inundation brought not just water, but rich black silt that created some of the world’s most fertile agricultural land. Without the Nile, there would be no pyramids, no hieroglyphs, no mummies – simply put, no Egyptian civilization as we know it.

We’ll explore how this remarkable river shaped every aspect of ancient Egyptian society. From religious beliefs centered around water deities to architectural marvels that still stand today, the Nile’s influence touched everything.

Geographic Foundation of Egyptian Civilization

The Nile River system created Egypt’s unique geography through its annual flooding patterns. Each summer, monsoon rains in the Ethiopian highlands caused the river to swell and overflow its banks. This flooding cycle deposited nutrient-rich sediment across the valley floor, creating the dark, fertile soil the Egyptians called Kemet – literally “black land.”

Division Between Kemet and Deshret

Ancient Egyptians understood their world in stark contrasts. The life-giving black soil of the Nile Valley stood in sharp opposition to the Deshret – the “red land” of the surrounding desert. This distinction wasn’t just geographical; it was deeply spiritual and cultural.

Farmers could literally step from lush, green fields into barren sand dunes within a few hundred meters. The contrast shaped Egyptian thinking about life, death, order, and chaos. The fertile Kemet represented life, growth, and divine blessing, while the Deshret symbolized death, the afterlife, and the realm of the gods.

Upper and Lower Egypt Geography

The Nile’s flow from south to north created Egypt’s unusual geographical naming system. Upper Egypt stretched from the First Cataract at Aswan to Memphis, following the river’s higher elevation in the south. Lower Egypt encompassed the Delta region where the Nile splits into multiple channels before reaching the Mediterranean Sea.

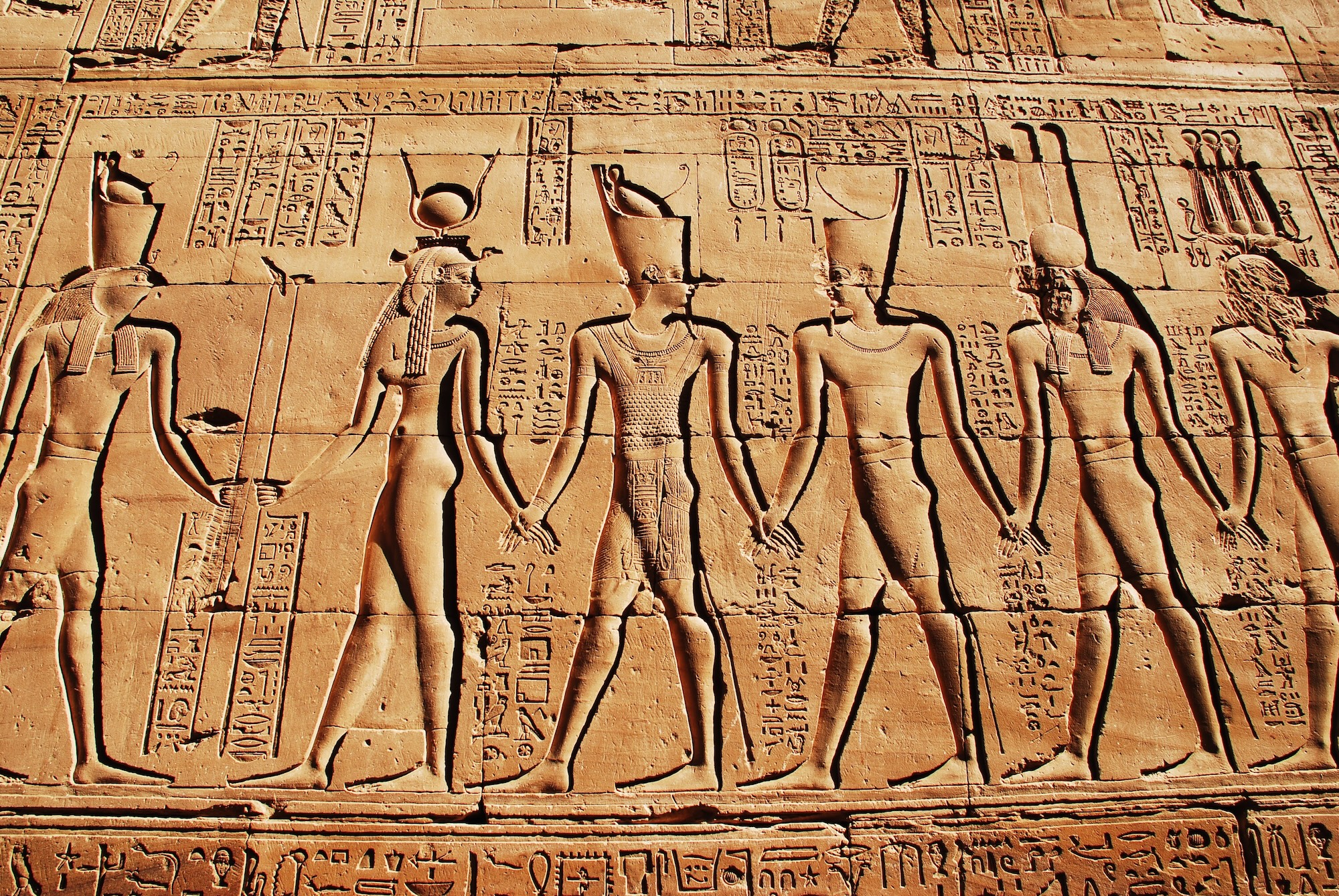

This geographic division became the foundation of Egyptian political identity. The pharaoh’s crown combined the white crown of Upper Egypt with the red crown of Lower Egypt, symbolizing the unification of these two lands. The Sema-tawy motif, showing the binding together of the two lands, appeared throughout Egyptian art and architecture.

Natural Boundaries and Protection

Six natural cataracts along the Nile created barriers that helped define and protect Egyptian territory. These rocky rapids made river travel difficult and served as natural fortifications against invasion from the south. The First Cataract at Aswan became Egypt’s traditional southern boundary, while the Delta marshes provided protection in the north.

Religious and Cosmic Significance

Ancient Egyptians saw the Nile as far more than a river – it was a divine force that connected the earthly realm with the cosmic order.

The god Hapi personified the Nile’s annual flood, depicted as a blue-green figure with pendulous breasts symbolizing the river’s nourishing abundance. Unlike many Egyptian deities, Hapi had no formal temples because the entire river valley served as his sacred space. Priests performed ceremonies directly at the water’s edge, making offerings to ensure the flood’s arrival.

Egyptian creation mythology placed water at the universe’s beginning. Nun, the primordial waters of chaos, existed before all creation. From these waters emerged the first land, much like the fertile silt islands that appeared each year as the flood waters receded. The Nile’s annual cycle thus reenacted creation itself.

Sacred Journey of Osiris

The myth of Osiris intertwined completely with the Nile’s geography and flooding cycle. According to legend, the god’s dismembered body parts were scattered along the river, with Isis gathering them for resurrection. The annual flood represented Osiris’s tears of joy at his resurrection, bringing life back to the land.

This connection made the Nile a sacred highway for funeral processions. Wealthy Egyptians often requested that their mummies be transported by boat along the river, following Osiris’s mythical journey to the afterlife. The western bank, where the sun set, became associated with death and burial, while the eastern bank represented rebirth and new life.

Agricultural Calendar and Egyptian Society

Three distinct seasons structured ancient Egyptian life, each tied directly to the Nile’s behavior. Akhet, the inundation season, lasted from July to November when flood waters covered the farmland. During this time, farmers couldn’t work their fields, so many joined pyramid construction crews or other royal building projects.

Peret, the growing season, began as flood waters receded and lasted through March. Farmers planted crops in the rich, moist soil left behind by the retreating waters. Barley and emmer wheat were primary crops, along with flax for linen production. The timing had to be perfect – plant too early and floods would wash away the seeds, too late and the soil would dry out.

Shemu: Harvest and Preparation

Shemu marked the harvest season from March through June. Farmers raced against time to gather crops before the next flood arrived. Royal scribes carefully recorded harvest yields for taxation purposes, making agriculture the backbone of the Egyptian economy.

During the dry months before the flood, communities worked together to maintain irrigation canals and prepare fields for the coming inundation. This seasonal cycle created a rhythm of communal labor that bound Egyptian society together. Village festivals and religious celebrations often coincided with agricultural milestones.

The predictability of these cycles allowed Egyptian civilization to flourish. Unlike Mesopotamia, where unpredictable floods could destroy crops, the Nile’s regularity enabled long-term planning and population growth.

Transportation and Trade Networks

The Nile River served as Egypt’s primary highway, connecting distant regions and enabling trade throughout the ancient world. Egyptian boat-building technology advanced rapidly to meet the demands of river transport. Early vessels used bundled papyrus reeds, but craftsmen soon developed wooden ships capable of carrying massive stone blocks from quarries to construction sites.

River Navigation and Patterns

Sailing north with the current required no wind, but traveling south against the flow demanded skillful use of prevailing northerly winds. Egyptian sailors developed triangular sails perfectly suited to catch these winds for upstream journeys. When winds failed, crews used poles or walked along the shore pulling boats with ropes.

The river’s seasonal changes affected navigation significantly. During flood season, boats could sail directly over normally dry land, reaching temples and settlements otherwise accessible only by long overland routes. Skilled pilots memorized underwater obstacles that appeared as water levels dropped.

Trade Routes Cultural Exchange

Nubian gold, African ivory, and exotic animals traveled north down the Nile, while finished goods, textiles, and manufactured items moved south. Trading expeditions ventured far upstream, beyond the traditional Egyptian borders, establishing relationships with distant African kingdoms.

Mediterranean merchants brought cedar wood from Lebanon, silver from Asia Minor, and precious stones from distant lands via Nile River routes. Alexandria became a major port where goods transferred between Mediterranean ships and Nile vessels, making Egypt a crucial link in ancient international trade networks.

Sacred Festivals and Rituals

Annual celebrations marked the Nile’s flooding cycle with elaborate festivals that reinforced religious beliefs and social bonds. The Wep Ronpet festival celebrated the Egyptian New Year, timed to coincide with the flood’s arrival and the heliacal rising of the star Sirius.

Beautiful Feast of Valley

One of Egypt’s most important festivals, the Beautiful Feast of the Valley, involved carrying divine statues from Karnak Temple across the Nile to mortuary temples on the west bank. Thousands of people participated in these processions, creating temporary bridges between the world of the living and the realm of the dead.

During the festival, families picnicked at ancestors’ tombs and shared meals with the deceased. The Nile crossing symbolized the soul’s journey to the afterlife, while the return trip represented the cyclical nature of life and death that the river embodied.

Nilometer Ceremonies

Sacred Nilometers at temples throughout Egypt measured flood levels with mathematical precision. Priests conducted ceremonies as water levels rose, making calculations to predict the flood’s height and duration. These measurements determined tax rates for the coming year – higher floods meant better harvests and higher taxes.

The most famous Nilometer stood on Elephantine Island at Aswan, where priests recorded flood data for over 1,000 years. These records provided crucial information for managing Egypt’s agricultural economy and became some of humanity’s earliest systematic meteorological observations.

Engineering Marvels and Innovation

Ancient Egyptians developed sophisticated irrigation systems to maximize the Nile’s agricultural benefits. Basin irrigation divided flood plains into large, flat areas surrounded by earthen banks. During floods, water filled these basins and remained trapped as river levels dropped, allowing crops to grow using stored moisture.

Canal Networks Water Management

Complex canal systems channeled flood water to distant fields and extended cultivation into previously barren areas. Egyptian engineers calculated precise gradients to ensure water flowed smoothly without eroding channel banks or depositing excessive sediment.

The Fayum region exemplifies Egyptian hydraulic engineering at its finest. Engineers diverted Nile water into a natural depression, creating Lake Moeris and transforming desert into Egypt’s most productive agricultural region. This project required advanced mathematical knowledge and coordinated labor from thousands of workers.

Architectural Alignment with River

Major temples and monuments aligned with the Nile’s cardinal directions, incorporating the river into sacred architectural plans. The Great Pyramid’s base aligns almost perfectly with true north, while temple axes often pointed toward significant Nile bends or the river’s source.

Mortuary complexes typically included harbors or canals connecting directly to the Nile, allowing funeral barges to deliver mummies directly to burial sites. The Valley of the Kings, despite being in the desert, connected to the Nile through elaborate processional routes that honored the river’s sacred geography.

Daily Life Along Riverbank

Egyptian villages clustered along the Nile’s banks, with houses built on higher ground to avoid flood damage. Wealthy families constructed elaborate villas with gardens extending to the water’s edge, while farmers lived in simple mud-brick dwellings designed for the river’s seasonal cycles.

Water Collection and Storage

Every household needed reliable water access throughout the year. During flood season, families collected and stored water in large ceramic jars. Wells provided water during dry months, though their depth varied based on distance from the river and local geography.

Professional water carriers earned their living transporting river water to homes and businesses located away from the banks. They used specially designed jars with narrow necks to minimize spillage and developed techniques for carrying multiple containers efficiently.

Women typically handled household water management, making daily trips to the river for washing, cooking, and drinking water. These journeys became important social occasions where community members shared news and strengthened neighborhood bonds.

Fishing and River Industries

The Nile teemed with fish that provided protein for all social classes. Fishermen used nets, hooks, and basket traps to catch various species, from small sardine-like fish to large Nile perch weighing over 100 pounds. Fish preservation techniques included salting, drying, and fermenting to create products that kept well in Egypt’s hot climate.

Papyrus manufacturing centered on the Delta’s marshy areas where this crucial plant grew abundantly. Workers harvested papyrus stalks, sliced them into strips, and pressed them into sheets that became ancient Egypt’s primary writing material. This industry employed thousands and provided a valuable export commodity.

Where civilization began — and stories still flow

Experience Egypt from land and water with our handpicked Egypt tour packages and elegant Nile River cruises.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long is the Nile River and how much flows through Egypt?

The Nile stretches 4,135 miles total, with approximately 600 miles flowing through Egypt from Aswan to Mediterranean.

What caused the Nile’s annual flooding in ancient times?

Monsoon rains in Ethiopian highlands caused Blue Nile tributary to swell, creating predictable floods reaching Egypt July-November.

Why did ancient Egyptians consider the Nile sacred?

The river provided life-sustaining water in desert, predictable flooding seemed divinely orchestrated, leading to worship of Hapi.

How did the Nile influence Egyptian agriculture?

Annual floods deposited fertile silt across farmland, creating natural irrigation supporting intensive agriculture in arid region.

What was the difference between Kemet and Deshret?

Kemet meant “black land” of fertile Nile soil, while Deshret meant “red land” of surrounding barren desert.

How did ancient Egyptians navigate the Nile River?

Wind-powered sails traveled south against current, drifted north with flow, developing sophisticated boat designs for seasons.

What role did the Nile play in ancient Egyptian religion?

River was divine highway connecting earthly and spiritual realms, with gods like Osiris and Hapi directly associated.

Why were there no bridges across the Nile in ancient Egypt?

River’s width, seasonal flooding, and sacred nature made bridges impractical; Egyptians relied on boats for crossing.

How did Nilometers work and why were they important?

Stone-lined shafts with markings allowed priests to gauge flood heights, predicting harvest yields and setting taxes.

What happened when the Nile’s flooding patterns changed?

Failed or excessive floods caused famine, economic collapse, political instability, demonstrating complete dependence on river regularity.

How did Aswan High Dam affect understanding of ancient Egypt?

Dam construction required massive archaeological rescue operations, leading to discoveries about Nubian cultures and Egyptian expansion.

Design Your Custom Tour

Explore Egypt your way by selecting only the attractions you want to visit