Abu Haggag Mosque – The Mosque in the Heart of Luxor Temple

Standing within Luxor Temple’s ancient walls, Abu Haggag Mosque represents something extraordinary.

This 13th-century mosque occupies a unique position in world heritage, built directly into the courtyard of Ramesses II’s pharaonic temple. For over 3,400 years, this sacred site has witnessed continuous worship through pharaonic, Roman, Christian, and Islamic periods. The mosque honors Sheikh Yusuf Abu al-Haggag, a revered Sufi saint whose annual mawlid festival draws thousands of pilgrims to Luxor’s East Bank.

What makes this place truly remarkable is how Islamic architecture seamlessly integrates with ancient Egyptian stonework, creating a living testament to Egypt’s layered religious history. We’ve guided countless visitors through this fascinating blend of cultures, watching them discover how modern devotion continues traditions that began when pharaohs ruled the Nile.

The Living Saint of Luxor

Sheikh Yusuf Abu al-Haggag arrived in Luxor during the 12th century from Damascus, carrying with him decades of Islamic scholarship and Sufi wisdom. Local legends describe how this holy man chose to settle in what was then the ruins of ancient Thebes, drawn by the site’s spiritual significance that had endured since pharaonic times.

The sheikh’s reputation for miraculous healing and spiritual guidance quickly spread throughout Upper Egypt. Stories tell of how he helped paralyzed pilgrims walk again and guided lost travelers safely to Mecca. His followers called him “Father of Pilgrims” because he prepared so many devotees for their sacred journey to the holy cities of Islam.

From Ruins to Sacred Space

When Sheikh Yusuf established his zawiya (religious lodge) in the 1180s, Luxor Temple lay partially buried under centuries of accumulated sand and debris. The Roman garrison had long departed, and Coptic Christians had abandoned their basilicas built within the temple walls. The sheikh recognized the spiritual power that still emanated from these ancient stones, choosing to build his prayer space where pharaohs once communed with the god Amun.

The Miracle of Integration

Unlike many Islamic conquerors who destroyed pre-Islamic monuments, Sheikh Yusuf embraced the existing architecture. His followers carefully carved a mihrab directly into pharaonic stones, creating prayer niches that pointed toward Mecca while preserving the original hieroglyphic inscriptions. This respectful integration established a precedent that continues today.

Death and Veneration

Sheikh Yusuf died in 1244 CE during the reign of the Ayyubid sultan As-Salih Ayyub. His tomb became an immediate pilgrimage destination, with devotees believing that prayers offered near his grave held special power. The simple dome that marks his resting place has been rebuilt several times, most recently during the 2009 restoration that preserved both Islamic and pharaonic elements.

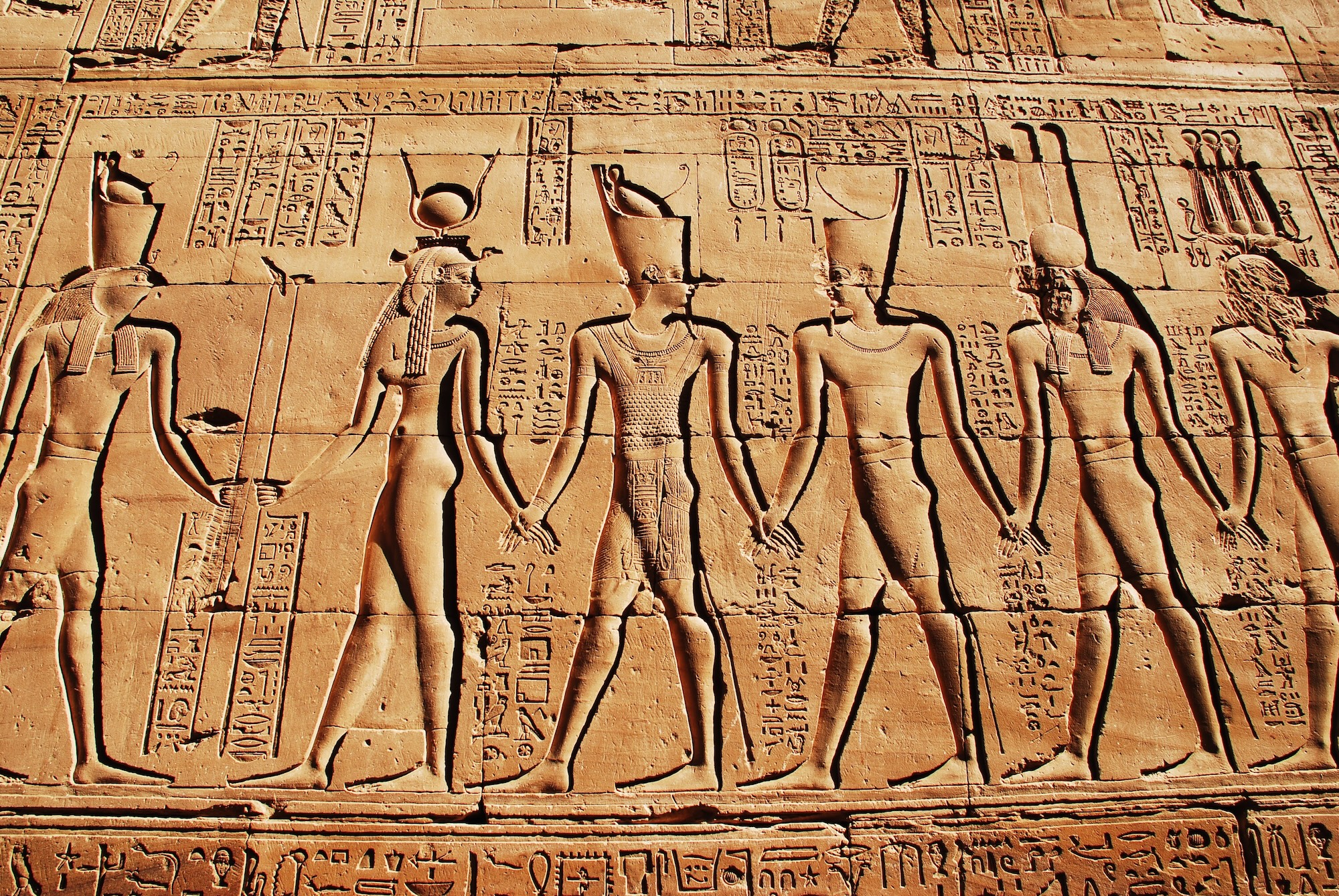

Architectural Wonder: Islamic Meets Pharaonic

The mosque’s architecture tells a story of cultural synthesis rarely seen elsewhere in the Islamic world. Two mudbrick minarets rise from the ancient temple courtyard, their Fatimid and Ayyubid styling creating dramatic contrast against the massive sandstone columns of Ramesses II. The main prayer hall occupies space that once housed sacred barks during the Opet Festival, while the mihrab is carved directly into walls bearing 3,000-year-old hieroglyphs.

Visitors often marvel at how the medieval builders worked around existing pharaonic structures rather than demolishing them. The mosque’s dome sits elevated above the temple floor, supported by a combination of Islamic arches and repurposed ancient stones. This careful integration required extraordinary engineering skill, as the builders had to account for the temple’s uneven levels and massive foundation stones.

The restoration completed in 2009 used traditional materials and techniques to preserve this delicate balance. Egyptian archaeologists worked alongside Islamic architecture specialists to ensure that both the 13th-century additions and the pharaonic foundations remained structurally sound. The project revealed fascinating details about how medieval Muslims adapted ancient Egyptian building techniques to serve their religious needs.

The Sacred Festival: Mawlid Abu al-Haggag

Every year during the month of Sha’ban, Luxor transforms as thousands of pilgrims arrive for the mawlid of Abu al-Haggag. This remarkable festival echoes ancient Egyptian traditions in ways that would amaze the pharaohs themselves.

Boats on Land

The festival’s most striking feature involves decorated boat-shaped carriages pulled through Luxor’s streets. These colorful processions mirror the sacred bark processions that once carried statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu from Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple during the Opet Festival. While the religious context has changed completely, the symbolic journey remains remarkably similar.

Community Celebration

Local families spend months preparing for the mawlid, decorating their homes and organizing neighborhood celebrations. Children receive new clothes, traditional sweets are prepared in abundance, and Sufi music fills the night air. The festival creates a sense of unity that transcends social and economic boundaries, bringing together wealthy merchants and humble farmers in shared devotion.

Spiritual Pilgrimage

Pilgrims travel from across Egypt and beyond to seek the sheikh’s blessing during the mawlid. Many believe that prayers offered at his tomb during the festival carry special weight, particularly for those seeking healing or preparing for the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. The mosque overflows with worshippers who come to touch the tomb’s marble covering and recite verses from the Quran.

Modern Relevance

Today’s mawlid demonstrates how ancient traditions adapt to contemporary life. While maintaining core religious elements, the festival now incorporates modern music, electric lighting, and social media documentation. Young Egyptians use smartphones to livestream proceedings for relatives abroad, ensuring that diaspora communities can participate virtually in this sacred celebration.

Visitor Experience: Exploring Sacred Space

Walking through Abu Haggag Mosque requires sensitivity to its role as an active place of worship while appreciating its incredible historical significance.

Practical Guidelines

We always advise visitors to dress conservatively when entering the mosque. Men should wear long pants and shirts with sleeves, while women must cover their arms, legs, and hair with a headscarf. Shoes must be removed before entering the prayer hall, so comfortable socks are recommended. Photography is generally permitted in courtyard areas, but never during prayer times or inside the main sanctuary without explicit permission.

Prayer Times and Access

The mosque follows standard Islamic prayer schedules, with five daily prayers that temporarily restrict tourist access. Morning visits between 9:00 am (09:00) and 11:00 am (11:00) typically offer the best combination of good lighting and minimal disruption to worshippers. Afternoon visits are possible between 2:00 pm (14:00) and 4:00 pm (16:00), though summer heat can make exploration uncomfortable.

Understanding the Space

The current mosque occupies roughly one-third of Ramesses II’s original courtyard. Visitors can clearly see where Islamic additions begin and pharaonic architecture continues, creating a fascinating study in architectural evolution. The imam or caretaker often provides brief explanations in Arabic or broken English, sharing stories about the sheikh’s life and the mosque’s significance to local families.

Respectful Tourism

Remember that Abu Haggag Mosque serves an active community of believers who consider this their spiritual home. Maintain quiet conversation, avoid pointing cameras at people in prayer, and consider leaving a small donation in the collection box near the entrance. These gestures demonstrate respect for the sacred nature of the space and help maintain the mosque’s upkeep.

Historical Context: 3400 Years Continuous Worship

This remarkable site represents one of the world’s longest continuously used religious complexes, with worship traditions stretching back to ancient Egypt’s New Kingdom period.

Pharaonic Origins

Amenhotep III began construction of Luxor Temple around 1400 BCE as a shrine dedicated to the Theban Triad: Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. Ramesses II later expanded the complex, adding the massive courtyard where Abu Haggag Mosque now stands. During the annual Opet Festival, elaborate processions carried divine statues from Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple, celebrating the renewal of royal power and divine blessing.

Roman Transformation

Roman legions established a military camp within the temple complex during the 3rd century CE. They built walls, barracks, and administrative buildings while leaving most pharaonic structures intact. Christian communities later converted portions of the temple into churches, creating some of Egypt’s earliest Coptic basilicas within the ancient walls.

Islamic Continuity

When Arab armies conquered Egypt in 641 CE, they found a religious site already sacred to multiple traditions. Rather than destroying existing structures, early Muslim rulers recognized the spiritual significance of continuous worship. Sheikh Yusuf’s decision to build his mosque within the temple walls honored this tradition while establishing Islamic presence in ancient Thebes.

Modern Archaeological Challenges

Contemporary archaeologists face complex decisions about preserving both Islamic and pharaonic elements. The mosque cannot be relocated without destroying its spiritual significance, yet its presence complicates full excavation of the underlying pharaonic remains. Current conservation efforts seek balance, protecting both traditions while allowing scholarly research to continue.

Cultural Significance: Past and Present

Abu Haggag Mosque embodies Egypt’s remarkable ability to honor diverse religious traditions within shared sacred spaces.

Symbol of Tolerance

The mosque’s peaceful coexistence with pharaonic remains demonstrates Islam’s historical respect for previous monotheistic traditions. Early Muslim scholars recognized parallels between ancient Egyptian spiritual concepts and Islamic monotheism, viewing sites like Luxor Temple as evidence of humanity’s enduring search for divine connection.

Living Heritage

Unlike museum artifacts, Abu Haggag Mosque remains vibrantly alive with daily prayers, weekly sermons, and annual celebrations. This continuity connects modern Egyptians directly to their ancestors’ spiritual practices, creating cultural bridges across millennia. Local families trace their devotion to Sheikh Yusuf back multiple generations, maintaining oral traditions about miracles and blessings associated with the site.

Educational Value

The mosque serves as a powerful teaching tool about Egypt’s complex religious history. Visitors learn how different faith traditions can respectfully share sacred space, creating layered meanings that enrich rather than diminish spiritual experience. Islamic calligraphy shares walls with hieroglyphic inscriptions, demonstrating how human artistic expression transcends temporal and cultural boundaries.

Tourism and Preservation

Increasing visitor numbers bring both opportunities and challenges for the mosque’s preservation. Tourism revenue supports necessary maintenance and restoration projects, but heavy foot traffic threatens delicate architectural elements. We work closely with local authorities to ensure that tourism benefits the community while protecting this irreplaceable heritage site for future generations.

Planning Your Visit: Sacred Experience

Experiencing Abu Haggag Mosque properly requires careful planning and cultural preparation, but the rewards are immeasurable.

Your visit begins at Luxor Temple’s main entrance, where entrance tickets include access to both the pharaonic complex and the Islamic mosque. We recommend starting with the temple’s ancient sections to understand the historical context before entering the medieval additions. This sequence helps visitors appreciate how Sheikh Yusuf’s followers integrated their religious needs with existing architecture.

Best Times for Photography

Morning light creates dramatic shadows across the mosque’s minarets and dome, highlighting the contrast between mudbrick Islamic architecture and sandstone pharaonic columns. The hour before sunset produces warm golden tones that enhance both the mosque’s spiritual atmosphere and photographic opportunities. During Ramadan or religious holidays, consider focusing on architectural details rather than worshippers engaged in prayer.

Combining Attractions

Abu Haggag Mosque pairs perfectly with visits to nearby Karnak Temple, creating a comprehensive understanding of ancient Thebes’ religious landscape. The 2-kilometer journey between sites follows the ancient processional route used during the Opet Festival, now lined with modern shops and cafes. Many visitors also enjoy exploring Luxor Museum, which contains artifacts from both pharaonic and Islamic periods found throughout the region.

Local Customs and Etiquette

Luxor’s residents take great pride in their mosque and welcome respectful visitors. Learning a few Arabic phrases like “as-salamu alaykum” (peace be upon you) or “shukran” (thank you) creates positive interactions with local worshippers and caretakers. During the mawlid festival, expect crowded conditions but also opportunities to witness authentic cultural celebrations rarely seen by tourists.

Our expert guides possess decades of experience navigating the cultural sensitivities surrounding religious sites while ensuring visitors gain deep understanding of Egypt’s layered history. We provide detailed orientation before entering the mosque, helping guests appreciate both Islamic traditions and pharaonic heritage that make this location truly unique in world tourism.

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Abu Haggag Mosque built?

The mosque was constructed during the 13th century CE (1200s) under Ayyubid rule, built directly into the ancient Luxor Temple complex.

Who was Sheikh Yusuf Abu al-Haggag?

A revered Sufi saint from Damascus who settled in Luxor during the 12th century, known as the “Father of Pilgrims” for his spiritual guidance.

Can tourists visit during prayer times?

Access is restricted during the five daily prayers, but visitors can explore between 9:00 am-11:00 am and 2:00 pm-4:00 pm most days.

What is the mawlid festival?

An annual celebration honoring Sheikh Yusuf held during Sha’ban month, featuring boat processions that echo ancient Egyptian religious traditions.

How old is the continuous worship at this site?

Religious activities have occurred here for over 3,400 years, making it one of the world’s longest continuously used sacred spaces.

What should visitors wear when entering?

Conservative clothing is required: long pants and sleeved shirts for men, full coverage plus headscarves for women. Shoes must be removed.

Is photography allowed inside the mosque?

Photography is generally permitted in courtyard areas but prohibited during prayers and inside the main sanctuary without permission.

How does the mosque integrate with pharaonic architecture?

Medieval builders carved Islamic elements directly into ancient stones, creating mihrabs within pharaonic walls while preserving original hieroglyphic inscriptions.

What makes this mosque architecturally unique?

It combines 13th-century mudbrick minarets and Islamic domes with 3,000-year-old sandstone columns and pharaonic foundations in perfect harmony.

When is the best time to visit Abu Haggag Mosque?

Early morning (9:00 am/09:00) offers ideal lighting and minimal crowds, while late afternoon provides excellent photography opportunities before sunset.

Do I need a separate ticket for the mosque?

No, the mosque is included with Luxor Temple admission tickets, providing access to both pharaonic and Islamic architectural elements.

How long should I plan for visiting?

Allow 45-60 minutes to properly explore both the mosque and surrounding pharaonic remains, with additional time for photography and reflection.

Design Your Custom Tour

Explore Egypt your way by selecting only the attractions you want to visit